As gardeners, it’s often necessary to wear different hats for all the various jobs that tending a garden entails.

Depending on the day (and time of year), we’re site planners, task schedulers, laborers, builders, sowers, reapers, and all-around plant whisperers.

Even when you think you’ve dotted all your i’s and crossed all your t’s, things can still somehow go left. And then it becomes clear that you’ll have to don the detective hat, too.

Of all the things that can go wrong, one of the most puzzling is when your seemingly healthy plants aren’t producing fruit.

Raspberry shrubs aren’t especially finicky things, but they can sometimes grow and grow – sending out their prickly canes every which way – with little to no fruit at harvest time.

Your raspberry plants can’t tell you exactly what they need to thrive, but they sure can show you.

Here’s what to look for so you can solve the curious case of the unproductive raspberry bushes.

1. You’re Pruning Your Raspberries Incorrectly

Raspberries have a unique growth habit. The crown and root system are perennial, but the canes themselves are biennial.

Further complicating matters, raspberry cultivars are then divided into two categories – summer-bearing and everbearing – which require altogether different pruning practices.

So, the most common reason for non-fruiting raspberries is pruning your summer-bearing shrubs like everbearing ones, or vice versa.

If you’re unsure which type you have, here’s the quick run-down:

Summer-bearing types will produce green canes in spring, known as primocanes. Primocanes grow throughout their first year and then go dormant in the fall. In their second year, these canes will become brown and woody, now known as floricanes. The floricanes will bear flowers and fruit and die back to the ground after harvest.

Everbearing raspberries, on the other hand, will produce fruit on the tips of the primocanes in late summer to autumn in their first year. The upper portion of the cane that bore fruit will die back in late fall or winter. What’s left of the cane will overwinter and produce fruit as a floricane in the second season. The floricanes of everbearing types will have lower yields than floricanes of summer-bearing varieties.

How to prune summer-bearing raspberries:

The correct way to prune summer-bearing raspberries is to let the primocanes grow since they will be the providers of next year’s crop. Floricanes that have flowered and fruited should be pruned back after harvest, snipping the canes all the way down to the soil line.

How to prune everbearing raspberries for a single or double crop:

Pruning everbearing types for a single harvest every fall couldn’t be simpler. All you need to do is cut down all canes to ground level in winter. The primocanes that emerge in spring will provide loads of delectable fruits in the same season.

For a double crop, everbearing shrubs can be pruned in winter by removing the tips of the primocanes, two nodes below the dead portion. These eventual floricanes will produce an early summer crop in their second year, and in the meantime, the freshly sprouted primocanes will provide fruits later in the season.

2. The Soil is Too Heavy

If your raspberry plants look stressed and are failing to thrive, the next thing to look at is the soil.

Raspberries are very sensitive to wet or heavy soils with poor drainage. If the soil is waterlogged for more than a few days in a row, the roots will suffocate, and the affected plants will be stunted with weak shoots. The leaves may turn yellow prematurely and have scorched coloring along the margins and between veins.

Raspberry brambles situated in poorly drained soil also make them much more susceptible to root rot. In advanced cases, root rot will cause the canes to wither and die before harvest time. Fewer primocanes will emerge from the crown in spring as well, and the ones that do can wilt and die in their first season.

If this sounds familiar, you can diagnose root rot by digging up a wilting – but not yet dead – cane and scraping the outer layer of tissue from the roots. The inner tissue should be white; if it’s reddish-brown, there’s root rot.

Your raspberry bushes will always be at their best in fertile, well-drained, loamy soil with moderate water retaining capacity. Compost – the miracle maker it is – accomplishes all these things and should be worked into the soil of the raspberry patch every spring.

After a good rainfall or deep watering, check to see how your raspberry plot is draining. If the water accumulates on top and isn’t absorbed within 10 minutes or so, you’ll need to increase drainage.

Gardeners in rainy climates may wish to take it a step further and grow raspberries above the water table. Raspberries have quite expansive root systems but will happily grow in raised beds and deep containers as long as they are 2 to 3 feet above the ground.

3. The Plants Aren’t Getting Enough Water

On the flip side, raspberries kept in drier soil conditions will be none too pleased as well. Like Goldilocks, these bramble fruits don’t like too much and not enough, but juuuuust right.

Watering your plants irregularly or too little at a time will stunt their growth, resulting in shorter plants that will inevitably provide fewer berries at harvest time.

Raspberry fruits are mostly made up of water, and the plants need slightly more irrigation than most other garden crops. From the onset of flowering to the end of harvest, raspberries should receive about 1.5 inches of water each week.

The root system occupies the top 2 feet of soil so watering regularly is more beneficial than the occasional deep soak. Irrigate several times a week – particularly with young, newly settled plants – to ensure moisture seeps deep into the soil.

Raspberries also appreciate a layer of mulch. Apply wood chips, leaves, lawn clippings, or leaf mold to a depth of 2 to 3 inches around canes and crowns.

4. The Canes are Too Crowded

Unpruned raspberries will quickly become a gnarly mess of thorny brambles when left to their own devices.

Raspberries are super vigorous growers that need annual pruning and thinning to keep them confined to the plot. Giving raspberries room to grow also happens to improve fruit production, allows for better air circulation, keeps plants neat and tidy, and makes harvesting the little berries a whole lot easier.

Raspberry hedgerows

In hedgerow systems, raspberries will form a shrubby thicket in a line. At planting time, everbearing raspberries should be spaced 2 feet apart and summer-bearing varieties 2.5 feet apart, with 8 to 10 feet between rows.

After a season or two, raspberry canes in a hedgerow will start to fill in. Keep the row widths fairly narrow – between 6 and 12 inches for summer-bearing and 12 to 18 inches for everbearing – to make it easier to see and reach the fruit.

Keep the primocanes that pop up between plants and remove any that emerge between rows. From the primocanes you keep, select 4 to 5 sturdy ones per foot and thin out the rest.

Raspberry hills

The hill system refers to clusters of raspberry canes with space between the plantings. Instead of a dense hedge, plantings are kept as individual specimens.

At planting, space hills 2.5 feet apart with 8 to 10 feet between rows. Each cluster of canes in the hill should be restricted to a diameter of 1 to 1.5 feet. Remove all primocanes that grow outside of the hill and along pathways.

5. There’s Too Much Shade

Raspberries need at least 6 hours of direct sunlight each day to ensure optimal berry production during the growing season.

Though the more sun you can throw at your raspberries, the more fruit they will provide, these plants will also grow in partially shaded and sun-dappled locations. You’ll probably get less fruit at harvest time, and the berries may be smaller and a little less sweet.

If all you have available is a part shade location for your raspberries, try to plant them in a spot that receives sun in the morning and shade in the late afternoon. Raspberries will perform better in the cooler early sunlight with some protection from the hot afternoon sun.

6. It’s Too Hot

Hot days in the blistering sun can cause sunscald on the delicate fruits as they are forming. The individual segments of the berry (or drupelets) will turn white or clear when exposed to high heat and strong sunlight.

The sunscald spots are flavorless and perfectly fine to eat, so don’t toss the whole berry away. Once the weather cools, the brambles will go back to making normal-looking raspberries.

The dog days of summer can also make fruits ripen faster than you can pick them. Birds, squirrels, and other critters will waste no time in harvesting the berries themselves. Visit your plants, basket in hand, every day to ensure you don’t miss out on the fruit.

7. There’s a Fertility Problem

Raspberries need a steady supply of nutrients to send out so many canes and flowers and fruit.

As heavy feeders, the plants need to be fertilized each year. The primary nutrient for raspberries is nitrogen.

You’ll know your raspberries are content with their nitrogen levels when plants have dark green leaves. The first signs of nitrogen deficiency are pale green and yellowing foliage.

Compost is the best option for adding fertility to native soils. Apply it every spring 1 to 2 inches deep over the top of the soil in your raspberry beds.

To boost nitrogen specifically, scatter nitrogen-rich things like alfalfa or blood meal around the base of canes and crowns.

You can also make liquid fertilizers from weeds and other plants collected from your yard. Or, the most wonderfully passive solution – grow nitrogen fixers nearby to ensure a consistent supply of nitrogen at all times to your hungry raspberry bushes.

8. There’s a Lack of Pollinator Activity

If you’ve done everything else right, your raspberry canes should be blooming with masses of pretty white or pink blossoms in summer or fall. But when you have lots of flowers yet no fruit set – or the fruits that do develop are misshapen and crumbly – is an indication the blooms aren’t being properly pollinated.

When you look closely at a raspberry flower, you’ll see roughly 100 pollen-tipped pistils arrayed around the floral disk. Each pistil would become a single bump – or drupelet – in the raspberry fruit. With around 100 drupelets to each berry, if every single pistil isn’t pollinated, the resulting raspberry will be small, malformed, and fall apart easily.

Although raspberry flowers are self-pollinating, they still rely on pollinating insects to transfer pollen around and set the fruit. Bees are the raspberry plant’s main pollinator – both wild and domestic bees are responsible for 90% to 95% of their pollination.

Increase bee activity in your garden by cultivating their favorite flowers. These include rosemary, salvia, yarrow, lavender, sage, and many more.

Bees are ordinarily very attracted to raspberry blossoms. One reason they may prefer the nectar of other flowers in the vicinity is by overwatering raspberries during their blooming period. Overly saturated soil will thin out the nectar and water it down, making it less sweet and appealing to bees.

9. Your Raspberries Had a Rough Winter

There are dozens of raspberry cultivars available today, ranging from hardiness zones 3 to 9. The most cold tolerant varieties can survive temperatures as low as -40°F (-40°C).

Even if you’ve perfectly matched the raspberries to your hardiness zone, the plants can still suffer from injuries in winter that can prevent canes from producing fruit the following summer.

Generally, raspberries will overwinter just fine when exposed to consistently cold temperatures. If there are rapid fluctuations – say, a warm spell in late winter followed by a cold snap – the raspberries will not be able to acclimate in time.

Come spring, cold-injured plants will most commonly show damage at the tips of canes. In more severe cases, you’ll see damaged or dead fruit buds along the length of the cane. Fruiting lateral branches may not grow at all or will collapse and die back after a bit of growth.

Winter injury is most devastating for summer-bearing raspberries. Because these types only fruit on canes that are two years old, floricanes damaged in winter won’t bear fruit in summer.

There’s not much you can do about the weather, but you can insulate your raspberries, so they are better protected against unusual swings in temperature.

In fall or after the first hard frost, apply a thick layer of mulch around canes and crowns to a depth of 4 inches. If winters in your area can be particularly harsh, consider bending canes down along the ground and covering them completely with mulch.

Planting raspberries in a spot that receives winter shade from nearby trees and shrubs can also help shield them from warming up prematurely.

10. Your Raspberries are Old and Tired

Everything has an expiration date, and raspberries are no exception.

Raspberry plantings will produce the most fruit between the ages of 5 to 15 years old.

When raspberry bushes are getting on in years, there will be a sharp decrease in fruit yields from one season to the next. Or there may be no fruit set along the canes whatsoever.

The canes will be shorter than in previous years, with fewer primocanes emerging in spring and weaker growth throughout.

Elderly raspberries also don’t have the same level of immunity as younger plants and will have less resistance against fungal and viral infections.

Thankfully, you don’t need to purchase new raspberry canes every decade – you just need to prepare for this eventuality.

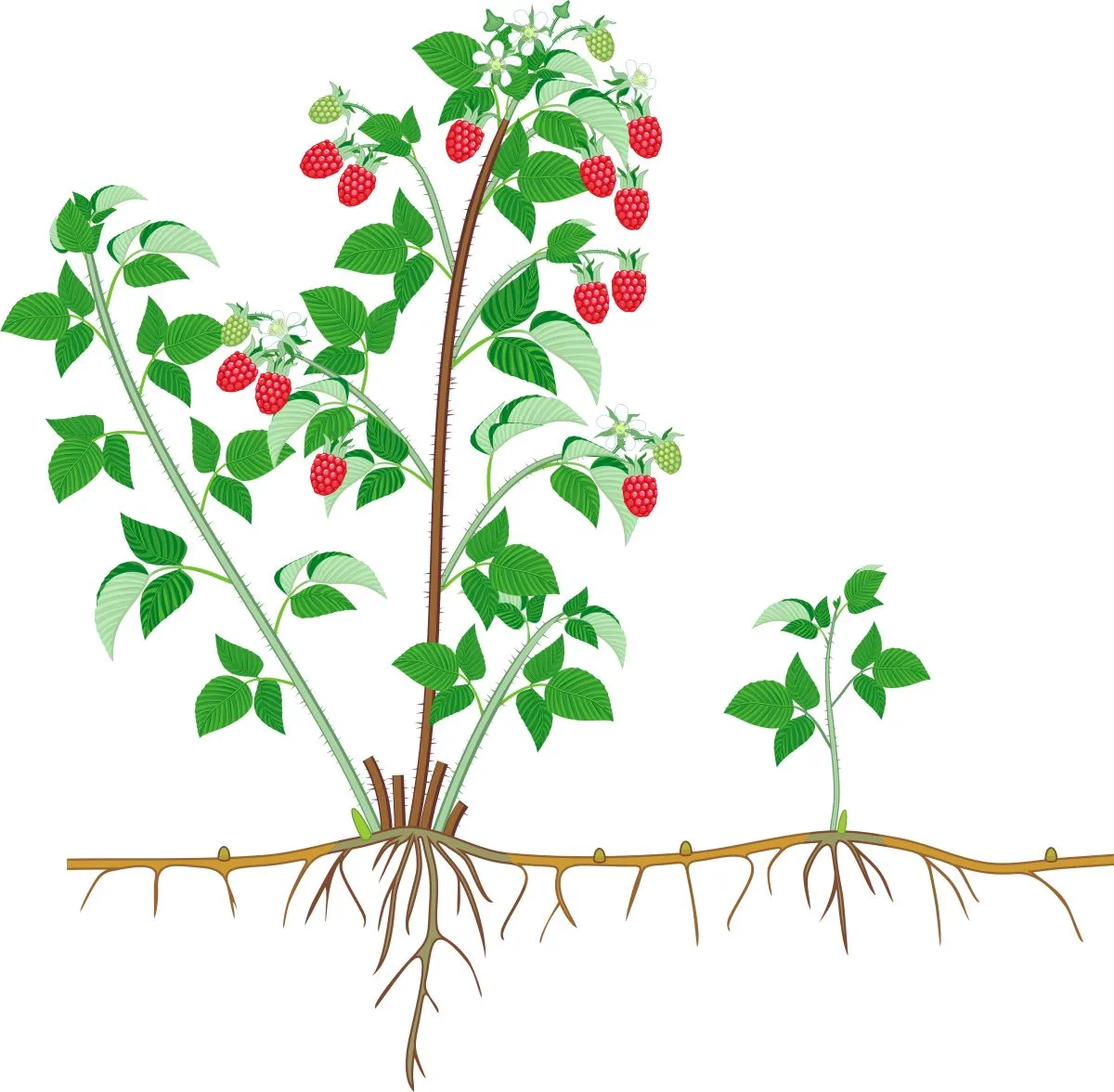

Raspberries are easily propagated by suckers – the basal shoots that run underground and pop up within 8 feet of the parent plant. Suckers are individual plants with a developed root system, similar to strawberry runners.

Dig up the suckers about six inches away from the shoot. Keep some soil around the root ball and sever the connection to the parent with a shovel. Plant the sucker immediately in a new spot.

Replanting a few suckers every year will make it so you’ll always have a good succession of productive raspberry canes.

Get the famous Rural Sprout newsletter delivered to your inbox.

Including Sunday musings from our editor, Tracey, as well as “What’s Up Wednesday” our roundup of what’s in season and new article updates and alerts.