Would you be shocked if I told you tomatoes are the most commonly grown vegetable in the world? Yeah, I didn’t think so; it’s no surprise here, either.

What is surprising are the adaptations tomatoes have made that enable them to grow nearly anywhere on the planet. And it all has to do with their hairy legs. Um, stems, I mean stems.

The hair on tomatoes isn’t some decorative fluke; it’s a highly responsive defense system comprising millions of trichomes.

That’s cool, Tracey; tomatoes have trichomes…what the heck is a trichome?

You may have noticed that unlike some of its other garden neighbors, tomato stems and leaves are fuzzy. Hairy. Downright downy. Believe it or not, these tiny hairs, called trichomes, are what enable tomatoes to thrive and grow so well.

I know, I know, we all know tomatoes are a bit fussy and prone to annoying diseases. But if they weren’t covered in trichomes, the tomato probably wouldn’t have made it off the Andes mountains and into everyone’s gardens.

What is a trichome?

The word trichome is derived from the Greek trikhoun, which translates to ‘cover with hair.’ Yeah, I know, not the most creative, but it’s accurate. In the simplest terms, a trichome is a growth coming out of the epidermal layer of a plant, usually hair-like. (There are also some algae, lichens and protists that have trichomes, too; it’s not just a plant thing.)

All those fuzzy hairs coming out of the stems, leaves, and even on the fruit of some tomatoes are trichomes, and they play a big part in how tomatoes (and other plants) sense and react to the world around them.

Tomatoes certainly aren’t the only plants in the garden with trichomes; peppers, sunflowers, beans and eggplants have them too. Most of us wish we were less familiar with stinging nettle trichomes. And everyone’s favorite controversial plant, cannabis, is covered with them.

Two Types of Trichomes

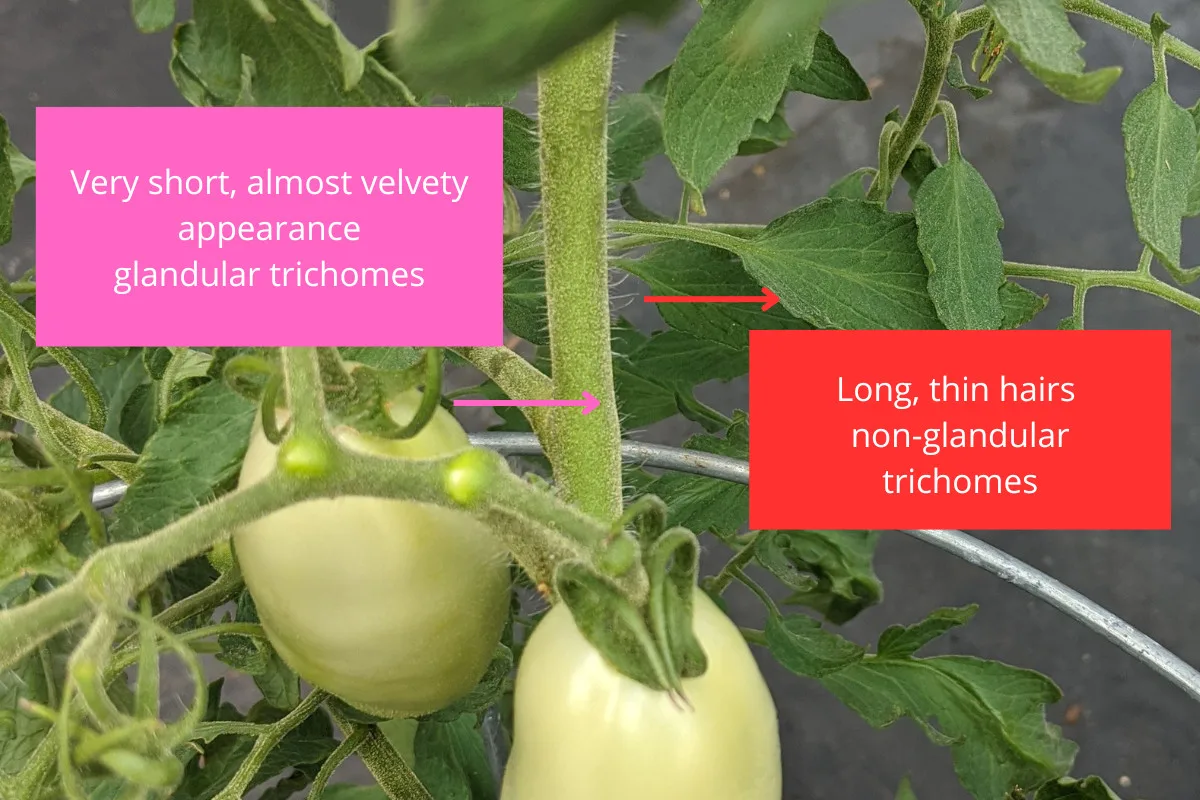

There are two types of trichomes – glandular and non-glandular. In plants, the glandular trichomes have a head at the end (often globe-shaded) that secretes something as a response to stress or a perceived threat. This secretion can be metabolites, essential oils, histamines, etc. Non-glandular trichomes are longer hairs with no head, and their primary function is to protect the plant from the sun and extreme temperatures.

Tomato Trichomes

Tomatoes have both glandular and non-glandular trichomes. Depending on the species, they can have up to eight different types, four glandular and four non-glandular, that all do different things for the plant.

Rather than fall down the scientific rabbit hole, discussing what the eight types of trichomes do and how the genes involved express different characteristics, we’ll keep this strictly in the garden. (Although, everything scientists have learned about tomato trichomes is pretty darn cool.)

A Natural Barrier

One of the trichomes’ most important roles is simple – they are a physical barrier between a tomato plant and the world. To us, they look like tiny hairs, but to a tomato plant, they’re as sensitive as a spider’s web is to a spider. They allow the plant to sense sunlight, temperature, and even when and where it is touched.

Not only do trichomes act as a sensory device, but they also prevent pests and diseases from reaching the plant. The tomato is basically covered in microscopic Velcro that can stop pests and pathogens from reaching the plant’s outer skin, whether to feed or infect.

Tomatoes Are All About Aromatherapy

Do you love the smell of tomato leaves? It’s one of those scents you love or hate, but every gardener knows exactly what I’m talking about. That unique scent is the result of glandular trichomes.

When you brush against a tomato plant, the globes on the glandular trichomes rupture, releasing a potent cocktail of flavonoids, terpenoids and sugars, aka essential oils. These oils serve numerous purposes.

- They have an unpleasant scent that deters certain pests.

- The chemical makeup is toxic to many insects.

- The oils contain an extra sticky, hydrophobic sugar that prevents insects from eating the plant or laying eggs on it.

- The oils can trap pests, effectively gluing them to the plant.

- They act as a barrier, locking in moisture and preventing the plant and fruit from drying out or cracking.

- The compounds in the oils are antiviral, antifungal and antibacterial, warding off disease.

You’ve probably witnessed this defense mechanism in action when working with tomato plants. Your hands become a yellowish-green when pruning them. Sometimes the oils are so thick and gunky that it turns black. You may have noticed how hard it is to wash this stuff off. I told you those sugars were sticky, but a little rubbing alcohol does the trick to break down the hydrophobic bonds.

Silvery Sunscreen and Hairy Legs are Warm Legs

The non-glandular trichomes are just as important. These trichomes are longer and usually have a silvery cast to them. This color and their density reflect the sun, acting as a physical sunscreen. Yup, even sun-loving tomatoes can get too much sun. The dense trichomes also play a role in making the plant more tolerant to drought conditions. Certain species of tomatoes have adapted to hot, sunny places by being extra hairy.

These long, shiny trichomes also protect the plant against UV-A damage, which can make them more susceptible to disease.

But non-glandular trichomes aren’t just a fancy way to beat the heat. Because they grow so densely, it’s almost like fine fur, which can also protect the tomato from light cold damage. Tomatoes with more trichomes may be less susceptible to catfacing.

Busting an Old Tomato Myth

Have you ever been told that the hairs on tomatoes will turn into roots if you bury them?

Nope, it’s not true.

As cool as trichomes are, they will not turn into roots when buried. However, when you plant tomatoes, you absolutely should bury them sideways or as deeply as possible.

That’s because all along the stems are specialized cells known as parenchyma cells. These cells are cool because they can change based on the plant’s needs. They can be used for photosynthesis, storing nutrients and water, or even turn into roots.

Planting a tomato sideways or deep will cause the parenchyma cells below the soil to divide and become what are known as adventitious roots or root primordia.

This can happen above ground, too, in certain weather conditions. You may notice tiny little bumps all over the stem. The parenchyma cells are dividing just below the epidermal layer, ready to grow into roots if needed. In times of drought, tomato plants will put out these ariel adventitious roots even if they aren’t underground.

So, no, tomato hairs won’t turn into roots, but parenchyma cells sure will.

When you think about all the pests and diseases stopped by trichomes, and all the ones that do make it past a tomato’s defenses, it’s pretty easy to see that tomatoes wouldn’t last long without those hairy legs. And they certainly wouldn’t be the world’s favorite vegetable to grow.

More Tomato Science

Get the famous Rural Sprout newsletter delivered to your inbox.

Including Sunday musings from our editor, Tracey, as well as “What’s Up Wednesday” our roundup of what’s in season and new article updates and alerts.