From roots and shoots to seeds and fruits, calcium is an essential nutrient that plays a crucial role in every single stage of plant development.

Calcium is a multi-functional mineral with more jobs than any other one nutrient. It hugely contributes to overall plant health, aiding in robust growth while also assisting with the uptake of nutrients. It creates strong roots, builds healthy soil, and oversees the immunity response in times of trouble.

Delivering the right amount of calcium to plants impacts every leg of the journey, from seedling to fully-grown cultivar. Get your calcium levels correct, and you’ll be well on your way to a successful and thriving garden.

Why Calcium is Essential for Your Garden

It’s taken more than 100 years of study to reach our current understanding of calcium’s role in plant health. It is involved in numerous intricate and complex mechanisms that keep plants growing.

Here are the fundamental ways calcium supports healthy plant life:

Plant Form and Structure

Calcium is the reason plants develop a strong physical structure – with branches and leaves and fruit – and aren’t just green puddles of goo.

It has a major role in the formation of cell walls and membranes of plants, influencing their plasticity, integrity, and permeability. It holds everything together like cement, keeping a plant’s form strong, thick, and rigid.

Nutrient Transport

Calcium also has a big impact on the transport – and thus, the absorption – of other essential nutrients.

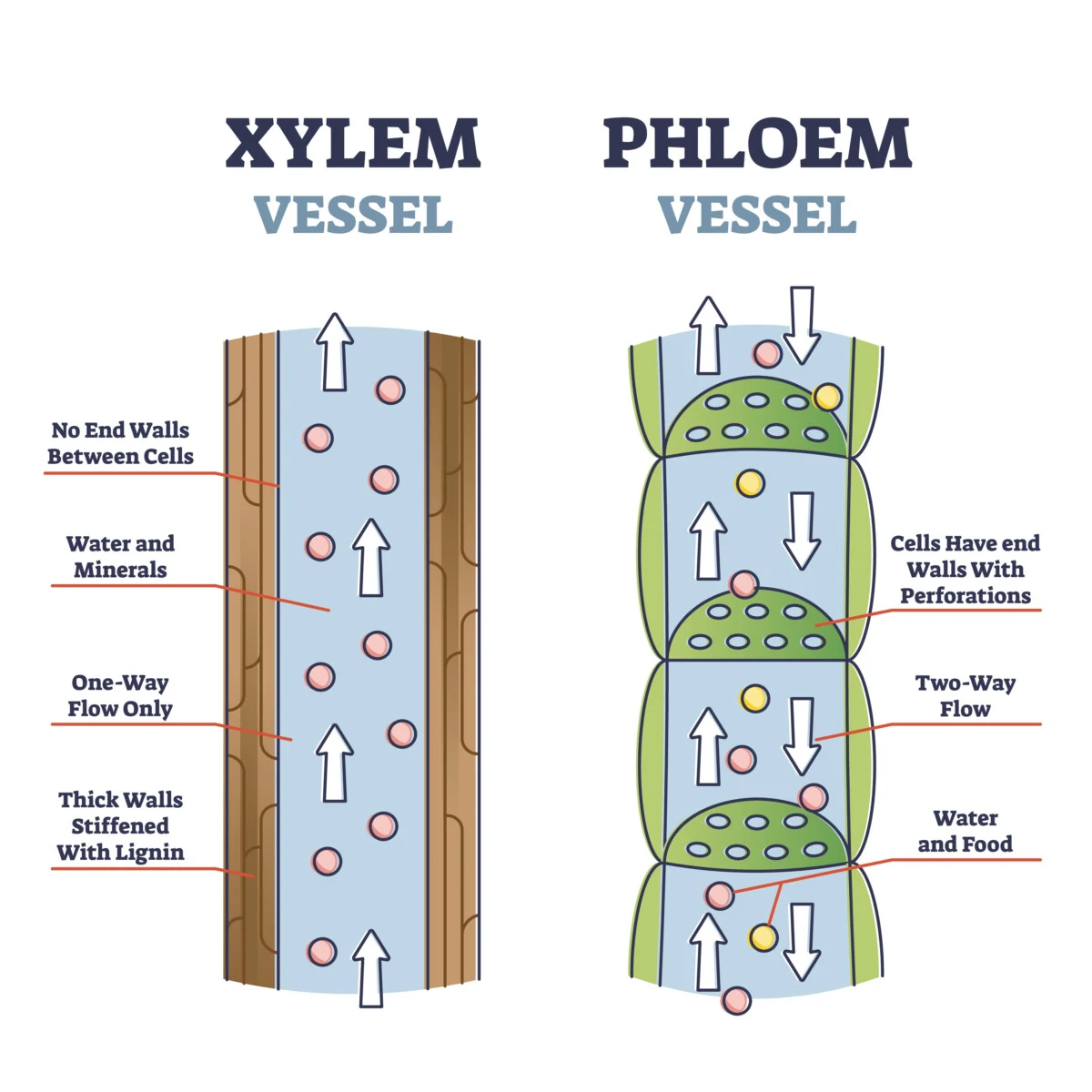

Since it’s our resident cell wall strengthener, it maintains the nutrient highway (the xylem and phloem) within the plant so that water, nutrients, and sugars can flow efficiently, from the roots all the way to the tips of leaves.

Root Development

Calcium is behind a variety of cellular processes that encourage strong and large root systems.

Certain proteins rely on a supply of calcium for root cells to divide and elongate correctly. It’s particularly important for the formation of root hairs – those tiny lateral outgrowths along root tips. These hairs vastly increase the root system surface area, allowing roots to make better contact with the soil and soak in more moisture and nutrients.

Reproductive Health

Calcium is essential for the plant’s ability to complete its life cycle.

Calcium is needed for the development of the pollen tube and the viability of pollen grains. It’s involved in processes that make it possible for fertilization to occur between the plant’s male and female reproductive organs.

Once a plant is pollinated, calcium bolsters the cell walls of developing seeds and contributes to seed coat formation.

During seed germination, it helps break down stored nutrients so that plant embryos have the energy to sprout.

In fruit-bearing plants, calcium is essential for harvests of the highest quality. The role it plays in cell wall strength creates fruits that have a plump and solid skin with a firm inner flesh.

Immunity Response

In addition to its job as a structural engineer, calcium is what’s known as an intracellular second messenger. It will relay signals when external physiological and environmental cues are met, triggering a cascade of events that deploy the plant’s internal defenses.

Calcium is among the earliest to respond to pests, diseases, and other sources of stress. The calcium signaling kicks off an array of protections, from defensive gene expression and the closing of leaf stomata, to the callousing over of injured parts and the pre-programmed death at infection sites.

Overall, plants with continuous access to calcium have a heightened resistance to stress – preventing a lot of damage from happening in the first place. Pests and pathogens are more likely to attack soft or weak tissues, but calcium makes it so plant cell walls are strong and fortified against invaders.

Soil Fertility

As essential as calcium is for plants, it’s an important mineral for soil health too.

Calcium contributes to the soil’s cation-exchange capacity – the ability to hold and release positively charged ions (cations) like calcium, potassium, magnesium, and iron for plants to use when needed.

It also builds healthy soil structure through soil aggregation. Calcium ions bind together soil particles into tiny clumps, creating spaces and channels within the soil for air and water to flow.

It’s an essential nutrient for soil life as well. Beneficial microbes – the bacteria, fungi, algae, and protozoa that create a healthy root zone – require a diet rich in calcium to grow, reproduce, and diversify. In return, they convert organic compounds in soil into water-soluble nutrients that can be taken up by plant roots.

4 Signs of Calcium Deficiency in Plants

To keep up with its important work of supporting healthy and productive growth in the garden, a steady trickle of calcium is needed from sowing to harvest.

Calcium is an immobile nutrient. Once it’s taken up by the plant, it’s quickly incorporated into the cell walls. Where mobile nutrients, like nitrogen and phosphorus, are stored and move from older to younger leaves as nutrients are needed, calcium gets fully absorbed. It doesn’t hop around to different parts of the plant.

As such, the first signs of calcium deficiency are localized – only certain parts of the plant are affected – and it occurs initially on younger leaves and new growth.

These are the most common ways calcium deficiencies manifest:

1. Leaf Tip Burn

Leaf tip burn on younger leaves is one of the earliest signs that your plants have received some – but not enough – calcium.

Older and more mature growth appears lush and healthy, but the newest foliage is marred by black or brown lesions at the very tips of leaves.

As the calcium deficiency progresses, tissue necrosis will proceed along the leaf edges and margins, then on to terminal buds and root tips.

2. Malformed Leaves

Calcium deficiencies also manifest in distorted, irregular, and all-round odd-looking growth.

New leaves emerge with cupped, curled, or crinkled margins. The foliage may be smaller than normal, twisted or deformed, with leaf tips that hook backwards.

Because calcium is involved in creating strong cell walls, new growth may stick together and tear apart as the leaves unfurl.

3. Stunted Growth

As the builder of plant structures, calcium sure does a plant body good. But without calcium to assist in cell elongation and division, plants are often much smaller and less productive.

Calcium-deficient plants are shorter, have fewer stems and growing points, and are less leafy overall. Stems might be brittle and break easily. The root system will likewise be stunted, with shortened root tips and limited root hairs. In some crops, it leads to premature bud and blossom drop.

4. Blossom End Rot

And then there’s the clearest indication that there is, indeed, a calcium issue in the garden: blossom end rot.

Blossom end rot begins as a darker water-soaked spot at the bottom of the fruit, opposite the growing stem. As the disorder progresses, the soft spot will dry out and turn into a hard and black lesion that can engulf more than half the fruit.

It primarily affects tomatoes, peppers, eggplant, zucchini, squash, watermelon, cantaloupe, and cucumbers. It first shows up on fruits while they are still immature, but in the rapid-growth stage.

This happens when there’s not enough calcium available to build firm skin and flesh. The fruit’s cell walls and membrane lose integrity and can no longer hold the skin together, causing the insides to leak out. The wet spot will eventually dehydrate, resulting in a sizeable dead zone on the lower portion of fruits.

How to Fix Calcium Deficiencies

Although calcium deficiencies are rare in nature, our intensively-planted garden plots can sometimes suffer from low calcium levels. This becomes especially apparent when growing calcium-hungry crops like tomatoes, peppers, and watermelon.

The quickest way to remedy inadequate calcium levels in soil is by amending your beds one of these calcium-rich granular supplements:

Lime is an excellent source of calcium carbonate with a fairly immediate impact on deficient plants. It’s an extremely alkaline material, however, that will raise the pH of your soil. It’s highly recommended to test your soil pH before and after applying lime in the garden.

Bone meal works a bit slower than lime in contributing calcium to soil, but it won’t raise up pH nearly as much. Along with calcium, bone meal includes high amounts of phosphorus and a bit of nitrogen.

Gypsum (also known as calcium sulfate) is a great fast-acting option. It’s one of the safest to add to soil because it’s neutral and has no effect on pH levels.

Wood ashes are a free source of calcium, potassium, phosphorus, and magnesium. It’s quite basic as well, so it’s best to use it sparingly to avoid throwing your soil pH out of whack.

Over the longer term, build up calcium levels in the soil slowly and gently.

Include eggshells, animal bones, and other source of calcium to your active compost heap. This ensures the finished compost will be rich in calcium once it’s ready to use.

Ground-up eggshells sprinkled over the soil around the base of plants works too – but it takes a quite a while for the shells to break down into a form of calcium that is available to plants.

Leaf mold is another mild amendment that contains a good amount of calcium, as well as a little bit of practically every other essential nutrient that plants need to grow.

If you’ve done everything right, but plants are still symptomatic – the cause is probably environmental.

More often than not, calcium deficiencies crop up – not from low levels of calcium in soil – but something else interfering with the plant’s ability to absorb it:

Acidic soil is one of the most common reasons calcium becomes less available plants. You can check your soil pH with an inexpensive testing kit like this.

Overwatering coupled with poor drainage limits the movement of oxygen and nutrients, including calcium. Improve drainage by amending beds with well-rotted compost and sand.

Prolonged drought will quickly stop calcium in its tracks, since water is necessary to transmit it through plant tissues. Make sure your plants receive at least an inch of water each week, especially during those dry spells.

Prolonged heat waves and cold snaps will throw plants into survival mode, where growth is slowed and nutrient uptake stops. Protect your plants with shade cloth and row covers to ease temperature-related stresses.

Nutrient imbalances can also impede proper calcium uptake. Nitrogen, potassium, magnesium, and iron compete with calcium for root absorption. High amounts of one or more of these competitors can cause plants to become calcium-deficient. Flushing soil with water will help leach out excess nutrients that could be hampering the uptake of calcium.

Get the famous Rural Sprout newsletter delivered to your inbox.

Including Sunday musings from our editor, Tracey, as well as “What’s Up Wednesday” our roundup of what’s in season and new article updates and alerts.