Gardeners – and especially those who garden organically – ought to be well-acquainted with nitrogen. As the N in N-P-K, it’s the first nutrient you’ll learn about as a budding plant grower.

You’ll encounter nitrogen again when you begin composting your kitchen and yard waste. It’s the “greens” that keep the pile hot and fuel the decomposition process. If you plant legumes, you’ll come to know about the nitrogen cycle and how specialized microbes around the roots pull nitrogen from the air and put it into the soil for surrounding plants to absorb.

Nitrogen is a part of multiple biological processes, an essential element for life and the food web.

It’s in the air, water, and soil. It’s contained within every living organism. So when you garden with natural systems in mind, you’re going to bump into nitrogen again and again.

In the plant kingdom, nitrogen is critical for plants to develop green leaves, capture sunlight – to photosynthesize – and gain the energy they need to flourish. Nitrogen is also involved in cell division and the creation of amino acids, so plants can grow ever taller and wider. It’s in the proteins and enzymes necessary for nutrients and water to be taken up through the roots.

It’s a primary macronutrient for good reason. Plants need nitrogen at all times and in all places, from the leaves and stems to flowers and roots. On the long list of essential plant nutrients, nitrogen occupies the top position because it’s used by plants in greater amounts than any other single nutrient.

3 Signs Your Plants Are Deficient in Nitrogen

As plants have such a large appetite for it, nitrogen deficiency is the most common nutrient problem gardeners will face. But luckily, it’s one of the easiest to recognize and remedy.

These are the three classic signs your plants aren’t receiving enough nitrogen:

1. Yellowing of Older Leaves

Plants with steady access to nitrogen will grow healthy and lush green leaves. When nitrogen is present in the soil, plants produce the green pigment chlorophyll and obtain energy from sunlight. Chlorophyll absorbs blues and reds in the light spectrum (it’s why we perceive plant foliage as green), and this light energy is converted into carbohydrates that are stored within the plant as sugars and starches.

When the soil is lacking in nitrogen, plants are unable to produce the chlorophyll they need for leaves to develop into a deep shade of green. And so chlorosis – or the yellowing of leaves – is the classic hallmark of nitrogen deficiency.

One of the earliest warning signs of low nitrogen is when older leaves toward the bottom of the plant turn yellow, while younger shoots and leaves remain green.

The initial yellowing of older growth happens because nitrogen is a mobile nutrient, and it moves around to different parts of the plant as needed. When the supply is limited, nitrogen is rerouted to support new growth. Often, the chlorosis will begin at the tips of mature leaves and progress back toward the stem.

As the deficiency advances and the accessible nitrogen is used up, the rest of the plant will turn a uniform shade of pale green to yellow-green, and sometimes, yellowish-white. In severe cases, older foliage withers and drops off the plant.

2. Poor Growth

Nitrogen is known as the nutrient for boosting vegetative growth, so plants will grow upwards and outwards with big leaves and numerous branches. Part of the reason nitrogen is so good for spurring development is its involvement in the creation of amino acids, the building block of proteins, which are essential for the normal functioning of cells and tissues.

The other reason is that vibrant green leaves can capture sunlight – but yellow leaves cannot. Without nitrogen to make chlorophyll, and chlorophyll to create the green pigment in leaves to absorb light, plants can’t photosynthesize. And without photosynthesis, plants won’t be able to produce the food they will need to fuel their growth and development.

Unable to generate sugary carbohydrates, the poor babies are literally starving. Malnourished plants will necessarily be smaller and appear stunted, weak, thin, and sickly.

3. Reduced Flowering and Fruit Set

A starving plant with chlorotic foliage will certainly be stressed. To increase its chances of survival, the plant will reallocate its limited resources to the most essential life functions.

Reproductive processes – such as flowering, pollen production, seeds, and fruiting – will be slowed or stopped while basic metabolic processes and root growth are prioritized.

Nitrogen-deficient plants will have a noticeable reduction in flowers and fruit. Some crops will have delayed flowering, while others will flower prematurely. Either too early or two late, low nitrogen levels affects the flower size, stem strength, color, and number of flowers per plant, leading to a yield and fruit size much smaller than you’ve come to expect.

How to Correct Nitrogen Deficiencies, Quickly

Fortunately, it’s not difficult to course-correct when you have a nitrogen deficiency on your hands. As nitrogen is mobile, once supplied to plants it will be readily wicked up and transported around to the parts that need it most. Even if your crops are a worrying shade of yellow, oftentimes the leaves will regain their lush greenness once nitrogen is applied.

Typically, the conversion of organic nitrogen into forms plants can use is a slow process but there are a few things we can do to hurry it along.

Firstly, having high microbial activity in your garden soil will hasten the breakdown of organic nitrogen into nitrates, making them available for plants to absorb.

Adding more organic matter to your beds will encourage and fuel more soil microbes. You can also brew up some aerated compost tea to crank up your microbe populations for faster nutrient uptake.

Secondly, foliar feeding will deliver this essential nutrient faster than through the soil.

While it’s not a substitute for good soil management practices, feeding the foliage bypasses the sluggishness of the root system to get nutrients into plants quickly. Spray both the tops and undersides of foliage and the nitrogen will be taken up through the tiny pores on the surface of leaves. These micropores close up in hot weather, so it’s more effective to apply foliar treatments in the morning or evening when temperatures are below 80°F (26°C). But it’s not a perfect delivery method, you can read why here.

And lastly, you’ll want to use fast-releasing sources of nitrogen.

Nitrogen flows through the ecosystem in several chemical forms, from ammonia to nitrites to nitrates, before it becomes usable by plants. Depending on environmental conditions, the process can take several weeks to many months to complete.

To cut that time down substantially, here are some readily bioavailable organic nitrogen fertilizers that have near-immediate plant uptake. With these, you can supply nitrogen to plants quickly – in a matter of hours or days, and not weeks or months:

Urine

The urine from mammals – including us – is an important feature of the Earth’s nitrogen cycle. We eat the nitrogen-rich plants, the body takes the nutrients it needs and then excretes the rest. Urine is mostly water, but it contains roughly 2% urea. Urea rapidly breaks down into nitrogen plants can absorb, and the cycle begins anew.

With an average N-P-K of 11-1-2.5, our pee is an excellent fertilizer. It’s especially plentiful in nitrogen, but also houses trace amounts of phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and magnesium.

Pure urine contains salts that can burn plant foliage and roots, so it needs to be diluted before you can safely use it in the garden. For a urine-soaked soil drench, dilute fresh pee with at least 10 parts water. For foliar treatment you can add to your pump sprayer, weaken urine with 20 parts water.

Fish Emulsion

Although the stench might bring a tear to your eye, fish emulsion is a terrific organic source of nitrogen that plants can quickly absorb.

Typically, fish emulsion has an N-P-K analysis of 5-1-1 and contains both slow and fast-releasing forms of nitrogen. It has proteins that degrade into nitrogen over time, but also contains ammonium and amino acids that are immediate forms of nitrogen that plants can soak up without delay.

Whether you purchase fish emulsion or make it yourself from fish scraps, dilute it before using it around plants at a rate of 1 tablespoon per gallon of water. Vigorously shake or stir together until the oily fish liquids are well-dispersed, then apply to the soil or spray it on plant leaves.

Blood Meal

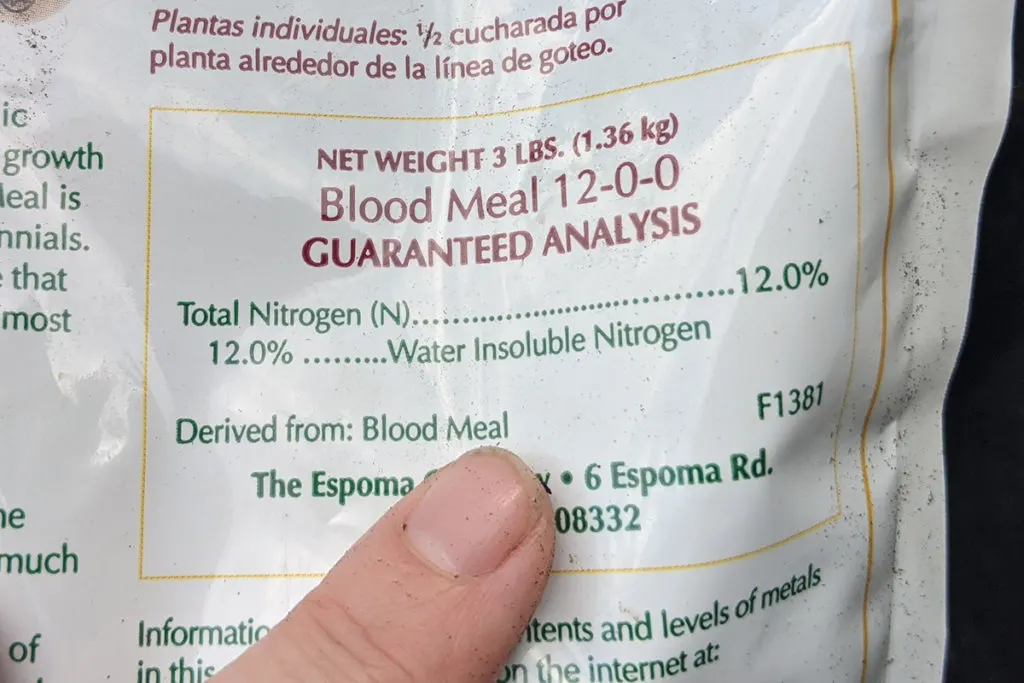

With an N-P-K of 12-0-0, blood meal is one of the very richest natural sources of nitrogen – though it’s often used in the garden as a slow-release fertilizer.

You’ll find most blood meal products on the market today in granular form, containing water-insoluble nitrogen. This is because blood meal is typically flash-dried during processing, which causes the liquid blood to coagulate into larger particles that won’t dissolve in water. Sprinkled over the soil and watered in, blood meal granules are broken down by soil microbes for a gradual release of nitrogen over 1 to 4 months.

For faster nitrogen release over a period of two weeks or less, look for unprocessed blood meal powder that contains water-soluble nitrogen. Blood meal powder will provide a quick nitrogen boost when applied to the soil or made into a liquid fertilizer. Be careful, though – excessive use of blood meal can burn plants and acidify your soil.

To make liquid blood meal, stir together 1 tablespoon of blood meal powder for every gallon of water. Pour it into the soil around the base of nitrogen-deficient plants, or spray it on the leaves. To avoid over-applying it, wait two weeks and observe the effects before treating plants again.

Managing Nitrogen in the Garden, Slowly

Naturally, organic materials tend to be slower-to-act than inorganic or synthetic fertilizers. Most will require an interaction with bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms before nutrients will be converted into bioavailable forms that plants can use.

Taking the slow and gentle approach to soil fertility has its advantages: better soil structure, improved drainage and moisture retention, and a healthier soil ecosystem all-around.

Nitrogen is essential in every stage of plant life, but it’s particularly crucial during the early, rapid growth of the vegetative phase. That’s the period before plants begin to flower and are busy pushing out more branches and leaves. Knowing when to supplement nitrogen is something that comes with experience, as you get to know the quirks and idiosyncrasies of the specific crops and cultivars you grow.

As a general rule, however, organic gardeners should plan to replenish N-P-K annually, in spring or fall.

Most of the time, applying these rich soil amendments will supply enough nitrogen to last the rest of the season:

Rich, well-rotted compost provides ample nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, along with a whole bunch of other welcome macro and micronutrients. Apply 1 to 2 inches of compost as a topdressing over your veggie beds every year.

Composted livestock manures – from cattle, sheep, or chickens – are rich sources of nitrogen, as well as other essential plant nutrients. Like compost, add 1 to 2 inches of aged manure once a year.

Alfalfa Meal

With a typical N-P-K analysis of 3-1-2, alfalfa meal sprinkled over the soil around plants will gradually release nitrogen for up to 4 months.

Feather Meal

High in only nitrogen, feather meal has an average N-P-K value of 12-0-0. It’s best for long-term soil fertility, since it releases nitrogen very slowly over a time frame of 4 months and longer.

A brilliant way to source nitrogen where it’s most abundant – the air – is to plant up beans, lupines, clovers, peas, and other nitrogen-fixing plants. As these species grow, they will draw nitrogen from the atmosphere and make it available as a soil nutrient. When legumes and the like die back over winter, they become a fantastic green manure, too.

Other Reasons Your Plants Have a Nitrogen Deficiency

Because nitrogen is used by plants in greater amounts than other nutrients, low levels of nitrogen in the soil is the most likely cause of yellowing leaves and stunted growth.

But, that’s not the only reason your plants are showing symptoms of nitrogen deficiency. Applying nitrogen once in spring or autumn won’t help fix these issues until you get to the root cause:

Soil pH is too acidic or alkaline. To take up nutrients like nitrogen, most plants require a slightly acidic to neural soil pH of 6.0 to 7.0. If adding nitrogen doesn’t seem to be helping, check your soil pH with a testing kit.

High amounts of rainfall or irrigation. Excessively wet soil causes nitrates to leach out of your garden beds and into the environment, especially if your soil is on the sandy side. To hold the nutrients in, add more organic matter to improve the soil’s water-holding capacity. Additionally, topdressing your vegetable beds with mulch and applying biochar will go a long way to retaining N-P-K in your soil.

They’re heavy feeders. Tomatoes, cabbage, broccoli, potatoes, cucumbers, peppers, corn, and melons are some crops that have a higher nutrient requirement for nitrogen. These heavy feeders might appreciate a second (and perhaps, a third) helping of nitrogen in the mid to late season.

Get the famous Rural Sprout newsletter delivered to your inbox.

Including Sunday musings from our editor, Tracey, as well as “What’s Up Wednesday” our roundup of what’s in season and new article updates and alerts.