Do you ever wonder if those of us who love houseplants are gluttons for punishment?

(No, Tracey, I don’t wonder. I know we are.)

We take beautiful tropical plants, most of which don’t grow anywhere near where we live, and bring them inside our dry, rainless houses and plunk them in a pot. Then we pull our hair out, trying to care for them so they will thrive in these unnatural conditions.

But that’s what we love, right?

The caring – tending and fawning over our foliage. And when our plants thrive, it’s like living in a gorgeous, green jungle. We get uncharacteristically attached to our houseplants.

My daughter has informed me I have houseplant grandkids in her apartment. I’m still not sure how to feel about that.

Of course, enjoying houseplants also means doctoring the occasional sick plant.

If you keep houseplants long enough, you’ll inevitably encounter root rot. This common plant disease is tough for even the most seasoned green thumb to spot until it’s well underway.

Because the damage is happening out of sight, with the roots hidden below the soil, by the time the plant begins to show signs of distress above ground, the roots are usually in pretty bad shape.

What is Root Rot?

Many believe that overwatering is the cause of root rot. And that’s partially true. Overwatering can drown and cause the root system to rot away. Your plant begins composting itself from the roots up.

However, we’re also talking about fungal and bacterial rots. And yes, overwatering is what kick starts these infections in your soil.

The most common root rot types you’ll encounter in houseplants are pythium root rot, phytophthora root rot and fusarium root rot.

Pythium root rot is a bacterial parasite that feeds on decaying plants. If you’ve got fungus gnats, you most likely also have pythium root rot, as gnats can carry it. Yay, fungus gnats and root destroying bacteria!

Phytophthora and Fusarium are fungi found naturally in the soil; there are several different species. Usually, these fungi remain dormant; however, they’ll become a problem with prolonged exposure to water (hello, overwatering).

It’s important to remember that these are all common organisms found in the soil, even potting soil, so trying to avoid them in the first place is nearly impossible.

How to Spot Root Rot

Root rot is one of the toughest plant diseases to catch early because the signs can be deceiving. Houseplants will begin to droop or wilt, and as any houseplant owner will tell you, your immediate instinct when seeing a droopy houseplant is to water it.

This is why I always recommend sticking a finger in your soil before you water a plant. Getting confirmation that the soil is dry before watering will prevent several common plant issues.

Your plant will begin to lose its healthy shine, and the foliage will become dull. And finally, the leaves and stems will begin to yellow or turn brown. And not the crunchy brown of a scorched or unwatered plant.

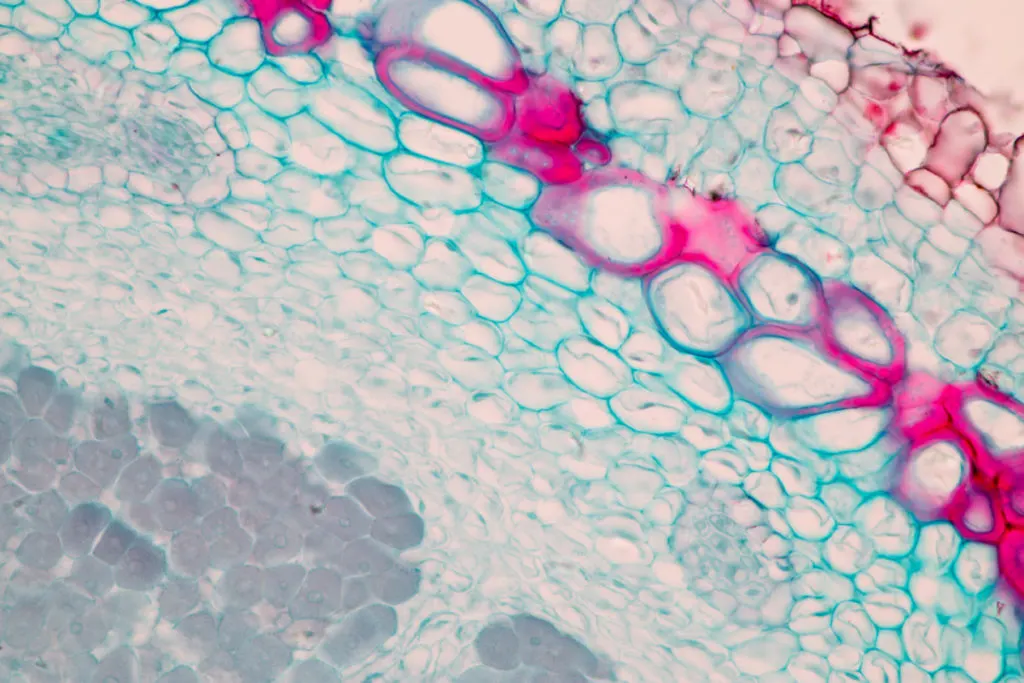

At this point, you need to gently remove the plant from the soil and inspect the roots. A healthy plant will have a large root system full of white- or cream-colored roots.

A plant infected with root rot will have brown or even black roots. Often, they will be mushy to the touch.

You may even notice the smell of rot. Blech.

How To Treat Root Rot

If you spot it early enough, you can treat root rot, but you have to move quickly.

Remove the plant from its pot, removing as much of the soil from the roots as possible. (This soil should be disposed of, not composted.) Run cool water over the root system to further remove contaminated soil from the plant.

Cutting Off the Damage

It’s important to use cleaned and sterilized tools as you cut away damaged roots and leaves. Rub your scissors or knife down with rubbing alcohol periodically throughout this process.

Be sure to clean your tools after trimming the roots and before moving on to the leaves. You don’t want to spread the disease further.

Now, begin by cutting away the diseased portions of the root system. If you need to cut away more than a third of the root system, a decision must be made. It’s unlikely the plant will survive. You can try cutting away more and see what happens, but it may not be worth your time and efforts.

Once you’ve finished with the roots, clean and sterilize your tools and trim away damaged foliage, take away as much foliage as you did roots – if you trimmed 1/3 of the roots, trim 1/3 of the foliage.

Trimming back the foliage of your plant makes it easier for the plant to recover. The roots don’t have to work as hard delivering nutrients to a larger plant with a diminished root system.

Fungicide or Hydrogen Peroxide to Treat Root Rot

You can treat the roots with a topical fungicide, such as organic Neem oil, or a water and hydrogen peroxide solution.

Mix one tablespoon of hydrogen peroxide with one cup of water and spray the roots down well.

Once treated, repot your plant into a new pot with fresh potting soil.

Throw out the remaining soil from the old pot, and clean the pot thoroughly with a water and bleach solution before potting any new plants in it.

Now We Wait

You’ll be able to tell how this story is going to end within a week or two. If your plant shows signs that it’s bouncing back, congratulations, you caught the root rot in time.

If it appears nothing is happening, be patient and give your plant more time to heal. However, if things continue to go downhill and your plant continues to look worse, it’s best to make the tough call and ditch the plant and soil.

Don’t forget to soak that pot in bleach water before using it with another plant.

Last Ditch Plant Cloning

If you’ve done everything you can to treat the root rot, and it still looks like your plant is tanking, take heart. Your houseplant may be able to live on through a clone.

Look for a healthy place to take a leaf or node cutting and propagate it using water or soil propagation. It’s a good way to keep special plants living on when the main plant is beyond saving. I’ve saved a Mother’s Day kalanchoe from my youngest and a holiday cactus that belonged to a family matriarch this way.

How To Prevent Root Rot

Here’s the thing, we often discover root rot once it’s too late. Yes, you can take measures to give your plant a fighting chance at healing itself. But as with most health-related issues, be it plants or people, prevention is key.

Hydrogen Peroxide

Hydrogen peroxide can be used as a way of boosting the oxygen in the soil. When you add hydrogen peroxide to your soil, H202, it breaks down, releasing its extra oxygen molecule and leaving you with water. The extra oxygen helps your plant take up nutrients and produce a healthy root system. It also kills bacteria and fungi in the soil.

To treat plants with hydrogen peroxide, use a solution of one teaspoon to one cup of water and water at the plant’s base periodically.

I’m not a huge fan of using hydrogen peroxide on my plants because it kills indiscriminately. It’s a bit like taking an antibiotic – not only do you kill the bacteria making you sick, you also kill off all the good bacteria in your gut microbiome.

For sick plants, I will use it as a last-ditch effort. But to encourage healthy plants, I much prefer to use…

Mycorrhiza

One of the best things you can do for your plants’ roots is to give them a partner in crime – mycorrhizae.

Mycorrhizae are beneficial microscopic organisms you can add to your potting soil. They’re kind of like probiotics for your plants. They’re usually fungi strains that cohabitate in your plant’s root systems, quite happily, unlike most roommates.

These tiny organisms grow around the plant’s root system, increasing surface area, making nutrient and water uptake easier, and holding moisture and soil in place. Mycorrhizae release enzymes into the soil, which break down nutrients making them more manageable for the root system. Most types of beneficial mycorrhizae outcompete other types of harmful bacteria or fungus.

Soil is a living entity, and plants that grow outside have access to the naturally occurring mycorrhiza colonies in the soil. However, because we’re growing plants in an artificial environment, we need to add these handy helpers to the soil.

The best way to do that is by mixing a quality mycorrhizae product directly into your potting mix before potting your plant. Well, thanks, Trace; if I had known that before, I wouldn’t need this post right now.

I know. But it’s something to keep in mind when you’re repotting plants or purchasing a new plant.

You can inoculate potted houseplants by poking some of the granules down into the soil with your finger. Some products can be mixed with water and added by watering your plant.

If you add mycorrhizae to your soil, be mindful that using hydrogen peroxide will kill off your beneficial microbes. Using hydrogen peroxide will mean you will need to inoculate your soil again.

Create a Weekly Plant Care Routine

I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again, you need a plant care routine. This is the key to healthy plants and spotting disease before it’s too late.

Pick one day a week and do it every week.

I’m not suggesting you water every plant. I’m just saying once a week, check-in with each of your plants, watering can and houseplant care accouterments in tow.

- Poke a finger in the dirt and see if it needs water.

- Check leaves for yellowing, brown spots, or the tell-tale webs of spider mites.

- Look at your soil and see if you have white mold growing or if you notice fungus gnats.

- If the soil is dry enough and you can do so without disturbing the plant, occasionally pull the entire plant up out of the pot (gently) and take a peek at the roots.

- Take a look under the pot; this is a great way to spot leaks and messes before they do too much damage to whatever your plant is sitting on.

- Wipe down leaves.

- Tell your houseplant how beautiful it is.

I like to do this on Sunday mornings after I’ve had my coffee. I find this quiet activity to be good for my plants and thoroughly relaxing for me too. If you choose Sunday as your plant care day, be sure to read the Rural Sprout Sunday Newsletter to your plants, it’s scientifically proven that talking to your houseplants is good for them.

Seriously though, stressed-out plants get sick. The best way to keep your plants happy and healthy is to pay attention to their environment. Checking in weekly is the best way to make sure a plant’s environment remains relatively stable.

In general, it’s best to underwater rather than overwater.

This is especially true in the winter when many houseplants go through a dormant phase, and their growth is slower. Most houseplants need less water during the darker, cooler winter months.

And that’s it, my friends, everything you need to know to treat root rot in your houseplants. It usually only takes the loss of one favorite houseplant to root rot before we arm ourselves with knowledge. I hope after reading this, you don’t lose anymore (or any at all) of your precious green potted babies.

Get the famous Rural Sprout newsletter delivered to your inbox.

Including Sunday musings from our editor, Tracey, as well as “What’s Up Wednesday” our roundup of what’s in season and new article updates and alerts.