If you’ve been gardening in the United States, you’ve probably consulted the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map at least once.

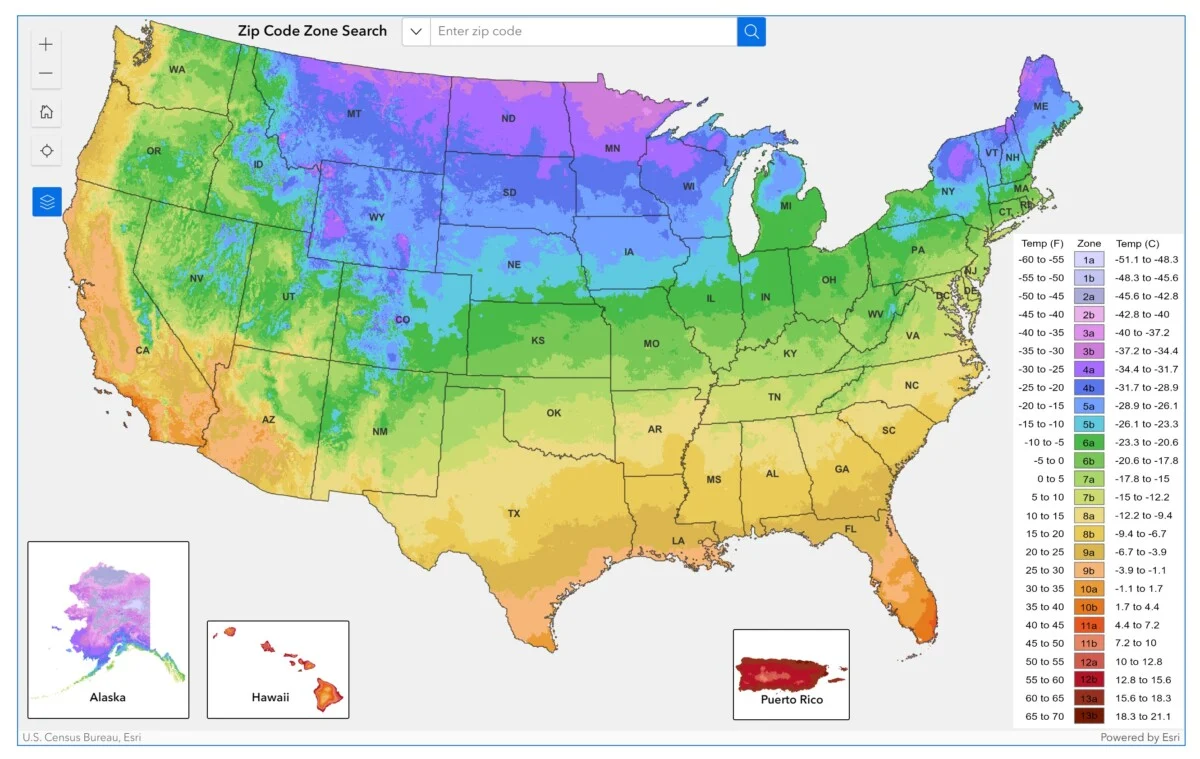

The PHZM or, as gardeners lovingly call it, the USDA gardening map is the standard yardstick in gardening. It helps us figure out what plants will thrive in our particular area by dividing the United States of America (including its territories) into 13 growing zones.

Up until this November, we were using the USDA map released in 2012. But in November 2023, the USDA released an updated version of the map. The new plant hardiness zone map has been developed jointly by the USDA and Oregon State University’s PRISM Climate Data Group.

Here’s what you should know about the new 2023 USDA zones map.

1. You can find more accurate information just by searching for your ZIP code.

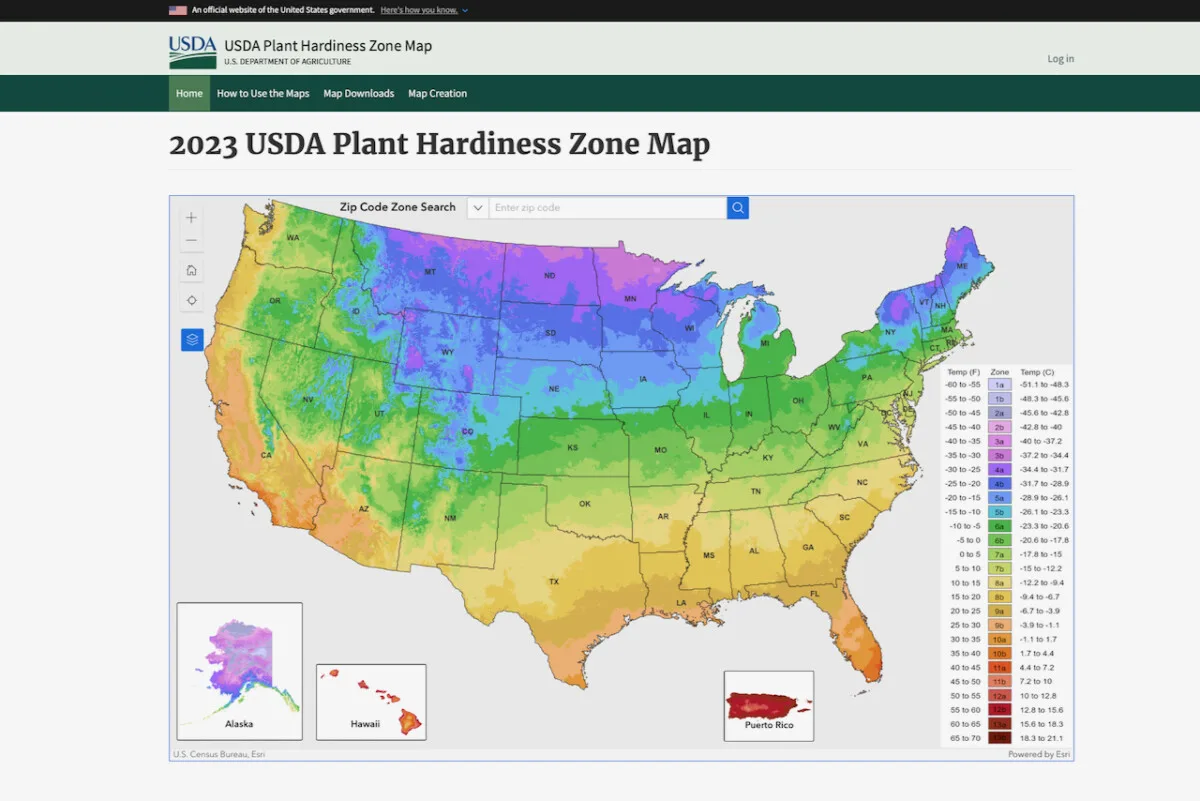

Here’s where you can find the updated USDA map:

https://planthardiness.ars.usda.gov/

You’ll see the official banner at the top that says “An official website of the United States government.” That’s how you know you’re in the right place.

Let’s start with the practical advice.

The 2023 version of the USDA map has been specifically designed for online use. So was the 2012 one, but in the most recent version, you can examine your zone at a finer scale.

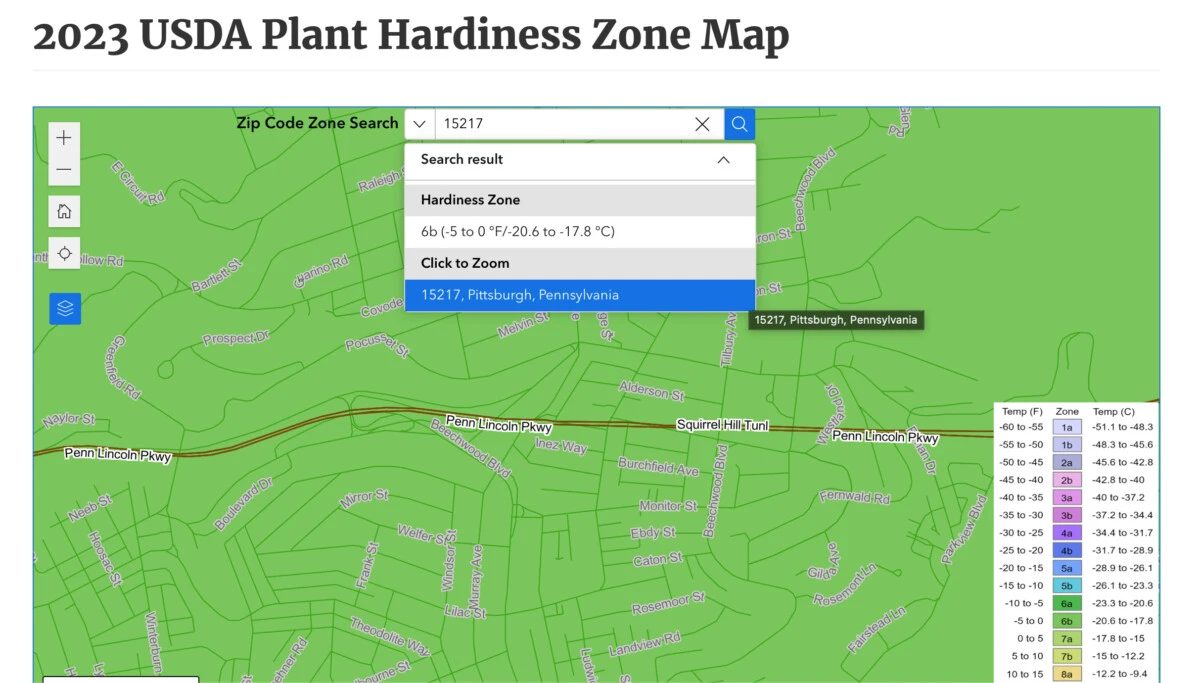

There’s no need to zoom in and out of your state to find your zone. Just type your ZIP code in the search box and you’ll get your zone, as well as what that means in terms of average minimum temperature.

For example, I typed in the ZIP code for my old neighborhood in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and found that it’s in zone 6b with an average minimum temperature of -5 to 0 Fahrenheit (that’s -20.6 to -17.8 Celsius).

There may be zone variations in adjacent ZIP codes.

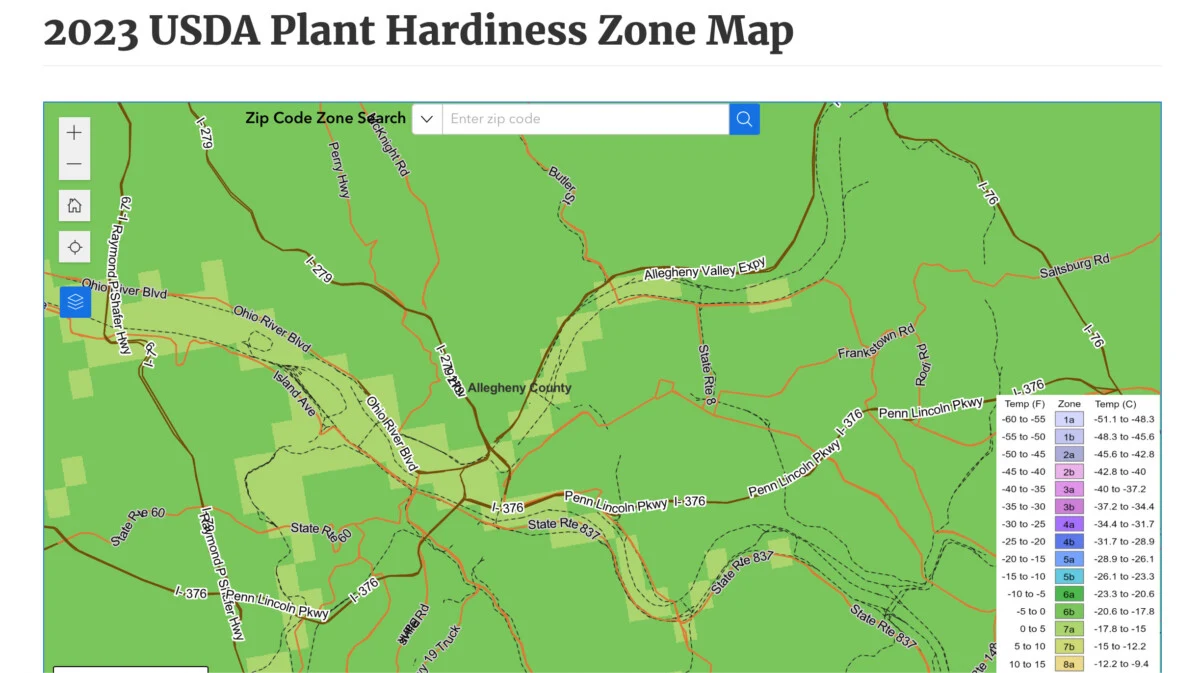

The complex algorithm used for the 2023 map accounts for factors such as changes in elevation and proximity to bodies of water (as well as position in relation to that body of water).

Taking these factors into account makes the mapping even more accurate. You can get down to about a quarter of a square mile in your neighborhood to determine your zone. (Just as a point of comparison, in the 2012 version of the map you could only get down to a six and a quarter square-mile area. So the new version of the map is even more precise.)

Using the same example as above, all I needed to do was zoom out of my neighborhood and notice the change in the gardening zone from 6b to 7a. So even within the same county (Allegheny County in Pennsylvania) and within the same city lines, we have two different gardening zones. This variation happens due to the modulating influences of the Ohio River and the Allegheny Valley. These areas experience slightly milder winter weather and therefore are in a warmer gardening zone.

So it’s always better to check your zone by inputting your ZIP code rather than just relying on a cursory look at the map.

2. The 2023 USDA gardening map is more accurate.

The 2012 map incorporated data from 7,983 weather stations. The 2023 updated map takes that number up to 13,412 weather stations. It relies on thirty years of data, measured at these weather stations from 1991 until 2020.

Scientists (horticulturists, botanists and climatologists) selected this longer period of time for the data in order to smooth out the year-to-year fluctuations in weather. This period of time (1991-2020) also aligns with the period that currently describes baseline climate “normals” in the United States.

What they looked at was an average of the lowest annual winter temperatures at specific locations. These averages are divided into 10-degree Fahrenheit zones and further divided into 5-degree Fahrenheit half-zones (called a and b).

Ok, I can already hear you yawn. Why is all this technical information important for gardeners anyway?

I think understanding the basic methods used to draw the map will dispel the following myth. (Or perhaps it’s a misunderstanding.)

The USDA map will not show us how cold it will get as an absolute in our gardening zone. It will show us a 30-year average of the lowest annual winter temperatures.

So let’s say we’re still in zone 6b. Remember that it has an average minimum temperature of -5 to 0 Fahrenheit. That doesn’t mean that it will never get below this temperature in our gardens. It might get below this temperature at any point during the winter months.

And it may very well kill our perennials, even though we thought they were zone-appropriate. The USDA zone map is just a helpful guideline, but it cannot be the be-all and end-all of gardening.

3. Your gardening (half)zone may have shifted.

The USDA map divides the United States and its territories into 13 different zones. Each zone is further divided into two half-zones, “a” and “b”. So zone 6, for example, is divided into zones 6a and 6b.

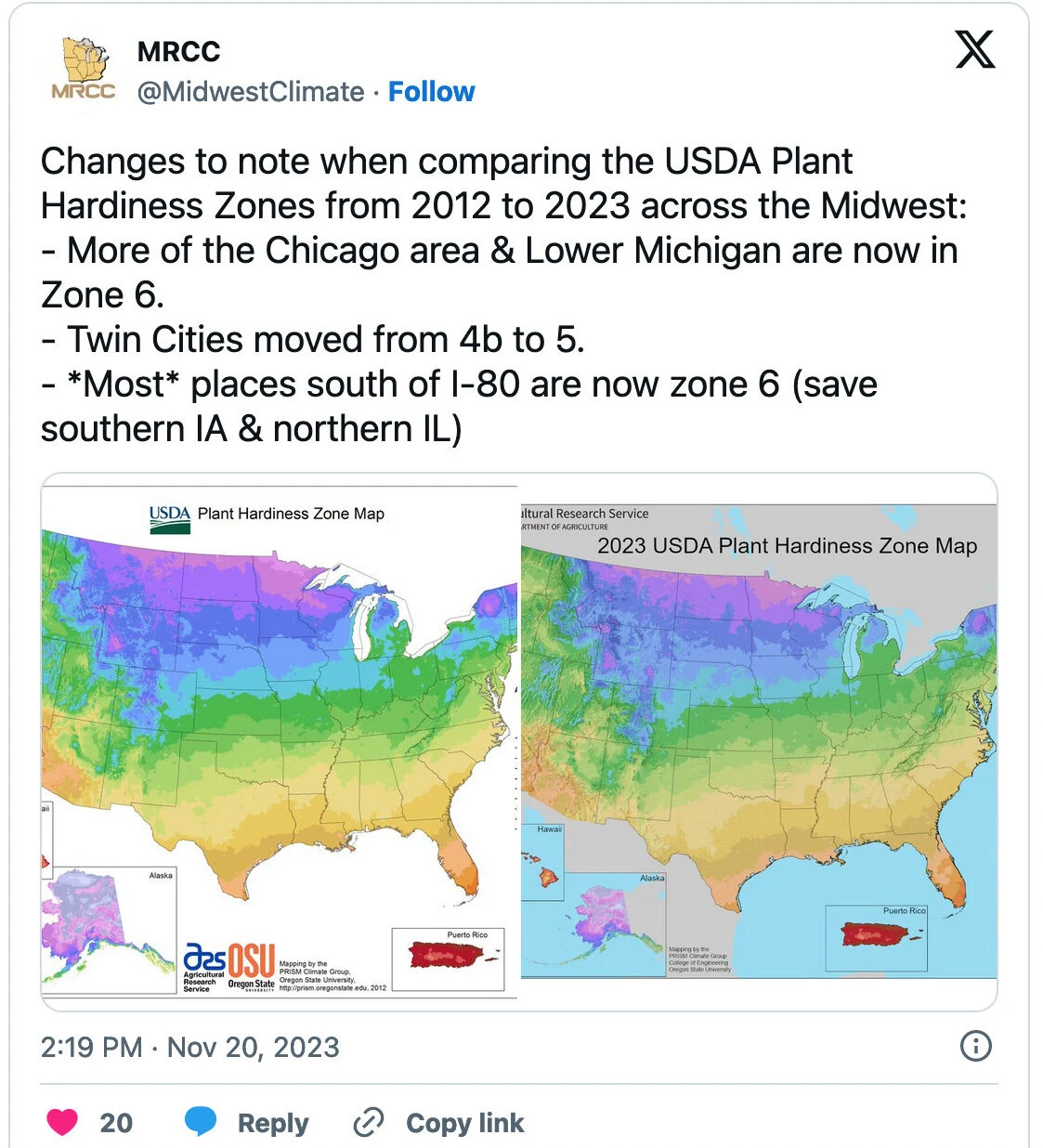

If you look at the 2012 and the 2023 maps side by side, you’ll notice that about half of the country has shifted to the next warmer half zone. This shows a warming trend of about 0-5 degrees Fahrenheit in those areas.

Let’s look at another example, this time put forward by the Midwestern Regional Climate Center at Purdue University on the social media platform X. They noticed that Twin Cities, Minnesota, moved from zone 4b to zone 5a. And that more of the Chicago area and lower Michigan are now in zone 6 (from zone 5b).

However, there are also areas that have stayed in the same half zone in 2023 as they were in 2012. This suggests that the warming is not uniform throughout the U.S. In some cases, even if there was warming, it wasn’t significant enough to shift the area into a new zone.

Overall, the 2023 map is about one quarter-zone warmer than the 2012 map throughout much of the United States. This is a result of the more recent averaging period (again, that’s 1991-2020).

Why does the USDA map matter to gardeners?

Knowing what USDA zone we’re gardening in can make the difference between a happy and productive garden and an endless list of disappointments and plants that are impossible to revive.

For annuals (and that includes crops), our zone influences how early we can start them from seed and then how soon we can transplant them into the garden.

But the importance of choosing plants appropriate for our gardening zones is even more evident in perennials. This includes trees and fruit bushes as well as perennial decorative plants.

Every time we choose to bring a new perennial into your garden, we have to make sure we’re matching the plant to the zone that we’re gardening in. Some plants behave differently in different zones. They may be perennials in a warmer zone, tender annuals in a more temperate zone and behave as annuals in a colder zone.

Knowing the finer zone details means that we won’t have to replace precious plants that we’ve optimistically planted in a zone that’s not appropriate for them.

Get the famous Rural Sprout newsletter delivered to your inbox.

Including Sunday musings from our editor, Tracey, as well as “What’s Up Wednesday” our roundup of what’s in season and new article updates and alerts.